"To each his own." Everyone has their own unique preferences, right? We're in complete control of what we like and what we don't like, right? No one can tell us what to think or do except ourselves, right? Well... what if I told you that, in the context of our social networks, we are all actually "copycats" - imitating our friends, conforming to expectations, and pining for what other people desire?

The Science of Social Networks Series will cover some of the more interesting insights and findings from the Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler book "Connected" and discuss how they might apply to marketers attempting to build closer connections with their consumers. In the final post in this series, Part 3, "Copycats", we'll take a look at how the actions and expectations of our social network influences what we do.

People Imitate Each Other

"No man is an island." It's true, don't you think? We're never truly alone: our social networks surround us both online and off. One of the consequences of always being a small part within a larger group is that many of the decisions that we make - what to eat, where to go, what to buy - are influenced by those around us. We imitate each other. And guess what, we choose to imitate each other. As social critic Eric Hoffer puts it, "When people are free to do as they please, they usually imitate each other." Iain Couzin of Princeton University looks at group dynamics from a different angle in his comments about shoals of fish from an article in The Economist, "If the models are anything to go by, the best outcome for the group—in this case, not being eaten—seems to depend on most members being blissfully unaware of the world outside the shoal and simply taking their cue from others."

Think back a few months, to the beginning of January. It's a time of New Years resolutions. One resolution that many people have is the desire to lose weight - by eating better, exercising more, and perhaps even going for a run (or aiming to go for a run) every day. You may have had one or more friends who made this proclamation and went about trying to lose weight. You yourself might have even been that friend. According to the authors of Connected, hearing that people are going for a run - just the thought of it - dramatically increases the odds that you or one of your friends will soon try running as well: "If you start a running program, then your friend might copy you and start-running; or you might invite your friend to go running with you."

"We are all capable of thinking with our heads, but our hearts keep in touch with the crowd."

Knowing this has a huge influence on how marketers might go about attempting to spread an idea, product, or behaviour. As the authors state, "Social networks generate behaviour that is not consistent with the simplified, idealized image of a rational buyer and seller picking a price to transact the sale of goods." But that, indeed, is how most marketers think of their consumers: as rationally-minded people plotting the pros and cons of their brand and its price while deciding whether to buy it or not. In fact, making activities, transactions, and "Likes" as visible as possible seems to be a more intuitive way of making a sale - of leading a sheep to the slaughter, to put it bluntly. Think about "Liking" brands and products via Facebook's ubiquitous "Like" button. It's not hard to fathom a future in which every single action or decision can result in a "Like" being broadcast to our network. Another way to allow people to publicize their behaviour is by allowing them to "Check-in" to places and retailers (ie. FourSquare), content like TV shows and books (ie. GetGlue) and even individual products (ie. ???). Making their actions public is key - because it increases the odds that their friends will copy them.

People Want to Conform to Expectations

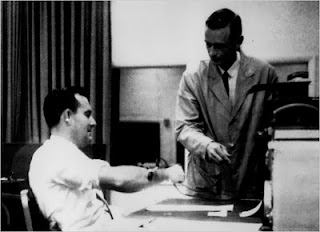

Another somewhat surprising, somewhat not-so-surprising insight from Connected: people will genuinely prefer to do what is expected of them, or what has been set out as the social norm, even if that action conflicts with their own individual preferences and beliefs. The authors illustrate this phenomenon with the story of Stanley Milgram's social psychology experiments at Yale University in 1963. In the experiment, a subject was placed in the role of the "teacher", with the job of helping another, unseen subject (the "student") learn. The "teacher" was instructed by one of the experiment's "researchers" to give the "student" a powerful electric shock every time they answered a test question incorrectly.

The reality is that this entire set-up was a charade: the "researcher" and the "student" were actors meant to test the "teacher's" tendency to conform to expectations and authority. As the "student" continued to answer the "teacher's" questions incorrectly, the electric shocks seemed to get worse and worse (the "student's" screams were, in actuality, faked). Many of the subjects who played the role of the "teacher" began to become increasingly distressed as the experiment went on and the screams from the "student" got louder. The reason that most "teachers" continued to shock the "students" is simple: the "researcher" would continually tell them that they were expected to continue or that the experiment required them to continue. To read more about Milgram's experiments, click here.

"[People] have a tendency to relinquish their decision-making to a group and to its hierarchy, especially when they are under stress."

Does this mean that we, as marketers, should be telling people that they must buy our products? Of course not! :) But the lesson from Milgram's experiment is that when behavioural expectations are set by an expert or authority figure - there's an increased chance that people will follow, regardless of their own desires. One area where this insight may be particularly useful is social marketing - attempting to shift social behaviour, like preventing teens from doing drugs or convincing people to recognize mental health as an illness. By setting expectations and letting people know how they should be acting, they may just follow suit.

People Want What Other People Want

The final insight into how our social networks influence our behaviour: people tend to desire what other people desire. When an object or situation is coveted by a certain group of people, it inherently puts pressure on other groups of people to covet it as well. As the authors put it: "Our judgement about the value and desirability of goods is thus similar to our judgement about the value and desirability of sexual partners: it depends on how others perceive the object of affection in question. Social pressures can drive demand."

In the same respect, being able to see what others thought of something can be a guide to how desirable that something is - and may thus influence what the succeeding people think about it. According to the authors, scientists found that in an experiment that asked the subjects to rate a given song, the first person's rating tended to influence the whole trajectory of ratings for particular songs. If the first reviewer rated a song relatively highly (and so, desireable), those reviewing the song after were more likely to also rate it highly. "Because of our tendency to want what others want, and because of our inclination to see the choices of others as an efficient way to understand the world, our social networks can magnify what starts as essentially random variation."

"Groups of animals often make what look like wise decisions, even when most of the members of those groups are ignorant of what is going on." -The Economist, Feb. 24, 2011

The lesson in this case is clear: one way for marketers to make their brands and products desirable is to make it clear that many people desire them - to make this desirability public. This need not only apply to brands and products, but deals and offers, too. Take Groupon, for example. Not only does passing on a daily deal to one's friends show that an offer is good - it shows that it's desirable. That, in turn, makes you want to get it, too. Shweet is an up and coming build on the Groupon model that aims to spread contests rather than deals. In order to be entered into a marketer's specified contest, one must tweet or share it (called "shweeting" it) with one's friends and followers. When the set number of "shweets" is met, the contest is activated. A meter below each contest shows the relative number of "shweets" - representing a contest's relative desirability.

Still believe in "to each his own"? As we've seen, we may be giving people too much individual credit when it comes to choosing how to behave and what to like or do. People tend to imitate each other. They'll tend to conform to the expectations and norms that are set upon them. They'll also tend to want the things that others want. And so, by making actions, behaviours, and desires as public as possible, marketers can tap into the power of... copycats.

Great post!

ReplyDelete